A, D, and E Chords

Using the rules I gave earlier, it's easy to set up these chords. In case you've forgotten them I'll briefly restate them:

- For the minor, take the third down a half tone.

- For the diminished, take the third down a half tone and the fifth down a half tone.

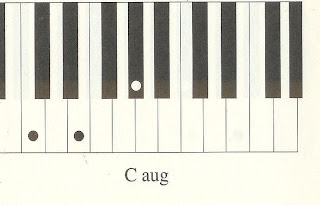

- For the augmented, take the fifth up half a tone.

For D-major we have D - F# - A - (D'), and from it we get Dmin as D - F - A -(D'). Dmin is a relatively common chord in songs written in C, F and G. Again, we can form Ddim and Daug in the same way; they are shown below. Finally, for E we have E major as E - G# - B - (E'), and Emin as E - G - B.

Bb and Eb chords

Chords associated with these keys have a distinctly different sound -- a ringing sound. And even though there are several flats in them, once you learn them, songs in either of them are just as easy to play as those in C, F or G. Let's begin with Bb; Bb-major is Bb - D - F - (Bb'), so Bb min is Bb - Db - F. Similarly, Bbdim is Bb - Db - E and Bbaug is Bb - D - F#.

For Eb we have Eb major as Eb - G - Bb - (Eb'), and Ebmin is Eb - Gb - Bb; Ebdim and augmented are shown below.

Something else you see occasionally in sheet music are symbols such as C/A. They are called a slash chords and important only in the base. The above one, for example, tells you to play a C chord with A as the bottom note.

Tenths in the Base

One of the best sounding chords in the base is the tenth. Tenths may be difficult for some people (with small hands) to play, but they are worth it if you can play them. A few stretching exercises may help if you have problems. Don't feel bad, though, if you can't play them, as there is a way around playing the two notes together (besides, they say that Chopin had trouble playing them and was always doing stretching exercises). Before we get to it, let's look at tenths themselves. A tenth is an octave plus a third; for C it is C - E' (E in the next octave). Similarly for F it is F - A, and for G it is G - B.

If you find the notes of tenths difficult to play together, you can "roll" them; in other words, you can play the lower note, then the upper note as quickly as possible.

Even better than two-note tenths are three-note tenths, but of course, they are even more difficult to play. In this case you add the fifth; so for C you would have C - G - E'. And again you can roll them. As a matter of fact, they sound particularly good rolled, so even if you can play them together, you should try rolling them occasionally.

A good place to use tenths is in the first beat of the bar, and they also sound particularly good in the first bar of the song. In the next lesson we will see that there are many things you can do with tenths to vary them, and they are, indeed, a good sign of a professional.

Other Chords

You were introduced to the seventh earlier (it is sometimes called the dominant seventh). There is another seventh that is used extensively by jazz musicians. It is referred to as the major seventh, and it is formed by adding the note that is a half tone down from the upper key note. In the case of C this is C - E - G - B -(C'); for F it is F - A - C - E - (F'), and for G, it is G - B - D - A# - (G'). You may find the sound a little dissonant at first, but as you play it more and more I'm sure you'll soon learn to like it.

So we now have the sixth, seventh, and major seventh, and any of them can be added to the minor, diminished and augmented. The most common addition, however, is the dominant seventh. With it you can form Cmi7, Cdim7 and Caug7, and in the same way you can form Fmi7, Fdim7, Faug7, and Gmi7, Gdim7, and Gaug7

Even though they aren't used much I'll mention a couple of other chords. We saw earlier that you can form the augmented chord, by upping the fifth by a half tone (it is designated as Caug or C+). You can also form a chord by lowering the fifth by a half tone (it is designated as C-)

And finally there are suspended chords. In this case the third is raised by a half tone. For C this is C - F - G.

Super Chords

The term "super chord" covers several different types of chords. Some of the above are frequently considered to be superchords, namely, the maj7, susp and two augmented chords. The major ones, however, are the 9th, 11th, and the 13th, and they are used extensively by jazz musicians. They may look like they're impossible to play, and indeed there are more notes in them than fingers in your left hand. We'll begin with the 9th; as the name suggest, it consists of the addition of the 9th, and usually the ninth is added to the seventh chord. In the case of C this would be C - E - G - Bb - D, which is an almost impossible stretch, so you will have to play some of the notes with the left hand. In fact, you can leave out some of the notes (and in most cases , you should) -- anything except D. For example, you could play E - G - Bb - D.

The next superchord is the eleventh, and it is formed by adding the 11th in addition to the 9th. And again, you will have to play some of the notes in the left hand. For the case of C, the 11th is C - E - G - Bb - D - F. Some people like the 13th, but I will not say anything about it; it's easy to see how it is formed.

Why would you want to use 9ths and 11ths? As I mentioned, they are used extensively by jazz musicians, so I guess you can say they "jazz up" your music. They do, indeed, give it a different sound.

Chord Substitutions

You won't see 9ths, 11ths and so on in the score of many songs. So how do you use them? This is where "chord substitutions" come in. Again, they are used extensively by jazz musicians, but in reality almost all professional piano players use them.

If you look at the chords in most songs you'll see that they are relatively simple; in most cases they are major and minor chords with an occasional diminished or augmented chord. Most professional piano players like to add in more complex chords to make the piece sound better. This is done by what are called "chord substitutions;" they are are changes in the chords that are shown on the sheet music. There are no rules for these substitutions, and the player has to use his or her ingenuity, but there are substitutions that are frequently used. Several of them are as follows.

- Quality Changes: In this case the root chord is used; in other words, if the chord is a C chord, you stick with it. But you can experiment with changes of type within the key. For example, you could try Cmi or C dim for C. In general: major -- minor -- diminished --augmented and sevenths can be used interchangeably. Your ear is the best guide. If it sounds good, use it.

- Add Notes to the Chord: You can add notes to any chord. You can also take away some of the regular notes that are in the chord (at the same time). For example, you could substitute C6 for C, C7 for C, Cmaj7 for C, or C9 for C, or C11 for C. And when you do it, you don't have to play all the notes of the new chord; in fact, it's a good idea to skip a few.

- Any Chord that Shares Several Notes With the chord Can be Substituted: If you look at C and G7, for example, you see that they share several notes. Also, Amin shares several notes with C, so it can be substituted for it.

- The Tritone Substitution: A tritone is three tones from the key note. In the case of G this takes us to C#, and it means you can substitute C# for G. An easy way to remember this is that the tritone is the flatted fifth. For F this is B, and for C it is F#. You can take this one step further in that you can substitute C#dim or any of the other similar chords for G.

- Stepping into a Chord: Any chord can be "stepped into" from above or below (usually a half tone above or below). For example, if you have a sequence of chords C, G7, you can step into G7 using an F# chord, so that you get C - F# - G7. You have to be sure, though, that there is room to add the extra chord.

- Add Extra Chords as Fillers: Earlier, I mentioned that you should try to add fillers to regions in the score where there are long notes. This is a good place to show your ingenuity. Play a sequence of chords -- any sequence that sounds good (I'll have more to say about sequences in the next lesson).

- The Best Advice: You can easily become confused when confronted by what substitution you should use. One of my early teachers gave me some advice that seemed strange at first (and made me laugh). But it works. He said. "Look at the second and third fingers in the octave chord you are playing -- move one or the other, or both up or down a note or two, and listen to what you get. If it sounds good, use it. You may not know what note you're playing, but it doesn't really matter.

Practise

- Practise playing inversions of the new chords : A, D, E, Bb and Eb,

- Play tenths. Begin with C, F, and G and two-note tenths. Gradually add in the fifth for three note tenths. Practise rolling them.

- Play inversions on Cmin 7, Cdim7, Caug7. Do the same thing for F and G. Also play sustained and augmented (+ and -) chords.

- Practise the superchords -- particularly the 9th and 11th.

- Memorize the basic rules (suggestions) for chord substitutions. Try adding new chords to some of the pieces you have learned. Try the tritone substitution and "stepping into a chord," and adding notes at random.