As I mentioned at the end of the last lesson, what you want is to make sure that every song you play doesn't sound the same, and isn't boring. And you do this by making up an arrangement. Your first arrangements don't have to be too elaborate, but they'll get you out of the rut of always sounding the same.

I outlined several things you can do that help in the last lesson, and I don't think it will take too long for you to realize the the number of possibilities is extremely large. You can vary the left hand by varying the pattern-- in particular, by varying the positions and numbers of single notes and chords. Similarly you can vary the right hand by using four-note, and three note chords along with thirds and so on, along with single notes.

"Voicing" The Chords

In this section I will have to write out the chords so you know what I'm talking about, but don't worry. This will be the only place you'll be reading more than a single line of notes. And I'm hoping it won't scare you. I'll try to keep it to a minimum.

"Voicing" means how you arrange the chord -- in particular, which notes of the entire chord you use. For convenience we'll think of the entire chord as the octave chord; in the case of C major (with the lowest note being C) it is C-E- G-C', so it's a four-note chord. It can, however, be a five-note chord such as C7, which is C-E-G-Bb-C'. Don't worry if you have trouble playing five-note chords (in most cases you won't have to).

Let's begin with the possibilities for C-E-G-C'; the major ones are shown below (where the key note is C')

You can use any of these for the melody notes. But aren't there any rules? you might ask. There are suggestions, but there are no rigid rules. Some of the suggestions are as follows.

- Don't use full chords for all melody notes. They will be difficult to play, particularly if the piece is fast, and they'll make the piece sound "too full."

- The three combinations that you should use the most are: full chord, octave, single note.

- The lead-in notes (before the first full bar) should be single notes, or octaves.

- The first note of the first bar should be a full chord. Also, most first notes of bars should be relatively full chords if they aren't short notes (e.g. eighths and sixteenths)

- Try for variety throughout the piece. In other words, use a variety of different chord types.

The best way to start a new piece is to "feel" your way through it with your right and left hands separately. When you have decided what you want you can bring them together. In the right hand, begin by experimenting with various chords. Keep the suggestions that I gave you earlier in mind. It's important to let your ear be the guide. If it sounds good and you like it, it may be what you want for your final arrangement. Also, when you find something you like it's a good idea to write it on the music in pencil so you remember it. You don't have to write out the music. Just use something like " full chord, or octave here" to remind you. If you decide later that you don't like it you can always erase it.

You will be playing the piece up one octave from where it is written. But when you play single notes, they don't necessarily have to be played up an octave. For example, in the above piece you can play the first middle C in its usually position, and the first note in the second bar as a full octave chord. The melody note is really up an octave here, which is okay. We'll continue by playing the E and G of the first bar as octaves, then we'll switch to an F chord using three notes of the chord. Also, use a three note chord for the next A, then switch to an octave for the last note in the bar. The following F in the next bar should be a full chord; then try something different -- use the partial chord shown, and follow it with the chord shown. Then back to a full chord on G.

Once you have an arrangement that you like, play it over until you can play it smoothly. You'll notice that the next eight bars have the same melody. You can play them the same way you did the first eight bars, but eventually you should try for some changes in them. I'll talk about that later. The arrangement below will give you some ideas.

Now for the left hand. For the most part you should keep it relatively simple at this stage. Remember the position of the three notes in the pattern I discussed earlier. It was a single note and two chords. Start with it, then add a few variations. When you've practised hands separately and have both down smoothly bring them together.

Fillers

In the above song it's easy to see that there are several bars that contain long notes. In some cases they extend over the entire bar, and may even go on for two bars. This is true of all music, and if you merely hold the notes through these bars, you are missing a good opportunity to show your skill and creativity. And the way to do this is add "fillers." There are obviously a large number of possibilities and we will only look at a few of them in this lesson. I will show you several things that you can easily add (in later lessons we will look at the topic in more detail). You can add fillers in both the right hand and left hand; for now we'll consider only the right hand. I'll start with what are called non-run fillers; as you will see later, they are generally a little simpler than run fillers.

Right-Hand Non-Run Fillers

Some of the simplest fillers of this type are sequences of dyads (two notes) They can be played in upward or downward sequences, or a combination of the two. One of the easiest is thirds; you could, for example, use the sequence shown in the figure on the left; it could also be play downward, as shown on the right. An interesting variation on this is an "echo effect" in which you play the three dyads in one octave, then play it in a higher octave. Make sure you keep the timing correct as you do it, however.

You can, in fact, play them anywhere there are long notes in the song. It's a good idea to stick to the notes of the key at first, though. Later you can add in a few "accidentals" (notes not in the scale) for variety.

Fillers like this don't have to be restricted to thirds. You can, in fact, use any of the following;

- 4ths (C and F in the C scale are a fourth apart)

- 5ths

- Octaves

Two other interesting fillers are simple scale patterns and single note patterns. In a scale pattern you play part of the scale either up or down (or both), usually in an upper octave. For variety you can vary the timing. One of the most creative patterns is the single note patterns; part of it can be a scale, but what you want to do is vary it in an interesting way. The best guide is your ear; try several patterns. When you find one you like, add it in.

Broken Chords

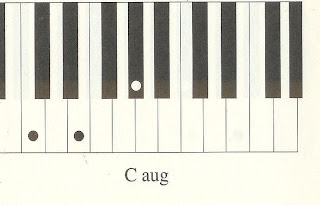

Broken chords are used extensively as fillers, and usually sound good. What is a broken chord? Previously we played all of the notes of a chord together; but you can play them in two groups. Consider the C chord; I'll assume we're playing the full octave tetrad, as shown on the left below.

You can also play the octave notes first, then the interior notes, as shown. This is a broke chord. In the same way, you could play C then the other three notes. There are obviously several possibilities. Referring to the fingers by numbers, we have: 1-235, 5-123, 123-5, and so on. A particularly useful broken chord is the broken triad shown below.

We'll see later that you can add several types of variations to these combination.

When you're making up an arrangement, it's a good idea to experiment with several types of fillers. Using the same type all the time can become boring.

Mix Them Up

There are, of course, a large number of combinations you could use. Some of them are:

- Several single notes up, thirds down

- Single note up, fourths down

- Use an echo effect with thirds (play in lower octave, then up an octave)

- Broken chords plus sequence of thirds

- Sequence of octaves down plus a few single notes

Runs

One of the flashiest types of fillers is the run. It is an octave chord that is broken up into individual notes played one after the other. For example, C major would be played as C-E-G-C', with each note played quickly after the preceding one. You have to be careful with runs, though; if you play too many the effect is lost. You can make octave runs sound even better by adding in the sixth or seventh; runs on diminished and augmented chords also sound great.

Runs can be played up or down, and they are frequently played in the upper register. I've only mentioned one octave runs here, but as we'll see later there are a large number of different types of runs, and they can extend across two or more octaves.

Fillers for the Left Hand

Fillers can also be used in the left hand. In the right hand they are usually referred to as melodic fillers; in the left hand they are called harmonic fillers. All of the things that I mentioned for the right hand can also be used in the left hand; this includes thirds, fourths, fifths and octaves along with partial scales and various single note patterns. They are not used as much in the left hand, but they can be helpful for variety. Runs can also be used in the left hand. Again, mix them up.

Practise

- Play a chord, then play several of the "voicings" of the chord -- in other words, play the chord with some missing notes. Try using some of these voicings in songs.

- Play thirds, fourths and fifths all over the piano in different keys. Get used to them. Practise adding them in several songs.

- Make up interesting single-note patterns. Listen to them carefully and memorize the ones that sound best. Do this for several different keys. Parts of the patterns can be scales.

- Practise broken chords of various types. Try 15 - 23, 1 - 235, 5 - 123, 1 - 35 (triad) and so on. Play them in different keys and in various places on the piano.

- Practise single octave runs up and down. Keep the even.

- Try mixing some of the above together.

- Experiment with using some of the above in the left hand.